All you need is Ecuador

Choose Ecuador as your holiday destination! This beautiful country is a paradise everywhere you look at it. Let yourself be amazed by its culture expressed majestically in its churches, buildings and heritage cities

For example, in Quito, discover the Best Preserve Historic Center in South America. In the Coast, you’ll fall in love with its views, beaches and the abundance of fauna that they enclose. Increase your adrenaline by practicing a variety of adventure sports that Ecuador has to offer. And do not forget to delight yourself with the taste of its gastronomic diversity, which you’ll find while touring this country full of magic and charm…

Live a unique experience, live Ecuador!

History of Ecuador

Pre-Spanish era

The area presently known as Ecuador had a long history before the arrival of Europeans. Pottery figurines and containers have been discovered that date from 3000 to 2500 BCE, ranking them among the earliest ceramics in the New World. Ecuadoran ceramic styles probably influenced cultures from Peru to Mexico. Early artistic traditions such as Valdivia, Machalilla, and Chorrera were of high quality, resulting in works of art that are on display in museums around the world.

By the 1400s Ecuador was divided into warring chiefdoms. Large populations were supported by sophisticated raised-field cultivation systems, and trade networks united the Costa (the Pacific coastal plain), the Sierra (the mountainous Andean area of central Ecuador), and the Oriente (the eastern region). Chiefs built large earthen mounds (tolas) that served as bases for their homes. However, Ecuador lacked cities and states until after the Inca conquest.

The conquest was begun by Topa Inca Yupanqui (ruled 1471–93) and extended by his successor, Huayna Capac (ruled 1493–1525), who lived much of his later life in Tomebamba. Although their cultural impact was otherwise spotty, the Inca spread the use of Quichua as a lingua franca and ordered large forced migrations where resistance to their conquest was especially strong. In Ecuador it is evident that Inca rule was resented by some and supported strongly by others. Huayna Capac left the Inca empire divided between his legitimate heir, Huascar, in Cuzco, and his son by an Ecuadoran Cara princess, Atahuallpa. This led to a territorial dispute, and Atahuallpa won the ensuing civil war after a major battle near Riobamba in 1532; at just about the same time, a Spanish expedition led by Francisco Pizarro appeared off the coast. Atahuallpa was executed the next year as the Spanish conquest spread. In many parts of what is now Ecuador, Inca rule was less than 50 years old, and many of the pre-Inca chiefdoms still held the peoples’ allegiance. As a result, the Spanish under Pizarro’s lieutenant Sebastian de Benalcázar were welcomed as liberators by some when they invaded Ecuador from Peru in 1534, while stiff resistance was encountered from others, especially the local leader, Rumiñahui, who was captured by the Spanish and executed in Quito.

The colonial period

During much of the colonial period, what is now Ecuador was under the direct jurisdiction of the law court (audiencia) of Quito and ultimately under the rule of the Spanish crown. Spanish culture was spread primarily by religious orders and male Spanish colonists.

In the Sierra, the Spaniards established a colony of large estates worked by Indian peons. Settlements included semiautonomous Indian villages and Spanish and mestizo administrative and religious centres such as Quito, Ambato, and Cuenca. The making of rough textiles in primitive sweatshops was the only industry. The development of Roman Catholic religious establishments provided for the flowering of Baroque architecture, sculpture in wood and stone, painting, music, and other arts and crafts.

In the tropical Costa, much of the population died as a result of introduced diseases, and the area remained unhealthy until the advent of modern medicine. As a result, the coast was somewhat neglected during the colonial period, although there was some shipbuilding and exporting of cacao (as cocoa beans) from the port of Guayaquil. The small coastal population of slaves, free blacks, and mixed ethnicities, with plenty of vacant land and less coercion of labour, developed a culture very different from that of the Sierra.

In the Oriente, the region on the eastern slopes between the Andes and the headwaters of the Amazon, large populations of Shuar and other indigenous people successfully repelled European invaders; however, Jesuits and other missionaries were able to spread both Christianity and the Quichua language. The Spaniards used Quichua as a language of evangelization—at one period missionaries were required to know the language—and continued to spread it orally by means of Quichua speakers who travelled with them in further conquests.

The country’s fourth major subdivision, the Galapagos Islands, were little more than pirate nests during the colonial period. They were to achieve world fame in the 19th century, because it was there that Charles Darwin made a major portion of the observations that led to his theories on evolution and his On the Origin of Species.

The people of Quito, the Ecuadoran capital, claim that it was the scene of the first Ecuadoran patriot uprising against Spanish rule (1809). Invading from Colombia in 1822, the armies of Simón Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre came to the aid of Ecuadoran rebels, and on May 24 Sucre won the decisive Battle of Pichincha on a mountain slope near Quito, thus assuring Ecuadoran independence.

Early national history, 1830–c. 1925

Ecuador’s early history as a country was a tormented one. For some eight years it formed, together with what are now the countries of Panama, Colombia, and Venezuela, the confederation of Gran Colombia. But on May 13, 1830, after a period of protracted regional rivalries, Ecuador seceded and became a separate independent republic.

People of Ecuador

Ethnic groups

The main ethnic groups of Ecuador include a number of Indian-language-speaking populations (often referred to as indigenous peoples or Amerindians) and highland and lowland Spanish-speaking mestizos (people of mixed Indian and European descent). Ethnicity in Ecuador is often a matter of self-identification. Most Ecuadorans consider themselves mestizo and tend to identify with their region of birth; the mestizo culture is highly regionalized. In the highlands, residents of Carchi (in the far north) and Azuay and Loja (in the south) have developed especially strong regional identities. An individual of Indian descent who has adopted European dress and customs can be classified as a mestizo or cholo (mestizo-Indian). There are also some Ecuadorans who speak only Spanish but consider themselves Indians. These include individuals living in traditionally indigenous districts in the Sierra and children of migrants to the city or the coast. Many people living close to the Pacific coast on or near the Santa Elena Peninsula no longer speak an indigenous language but still exhibit traces of indigenous customs and identity. Descendants of Africans and more-recent immigrants from a variety of foreign countries, including Lebanon, China, Korea, Japan, Italy, and Germany, make up the remainder of the population. Most modern censuses have not inquired about ethnicity, language, religion, or origin, so the numbers of different groups are not precisely known.

There may be about one million Indian-language speakers throughout Ecuador, most of whom live in the Sierra and speak Quichua, a dialect of Quechua. The highland Quichua speakers, many of whom are bilingual in Spanish, have only recently come to identify themselves ethnically with regions beyond their local villages; they often refer to themselves as Runa (“People”). They are concentrated in several distinct districts: to the north of Quito, in the vicinity of Otavalo and Cayambe; and in the central highlands, from the vicinity of Latacunga to beyond the southern border of Chimborazo provincia (province). These groups include the distinctive Salasacas people, who live south of Ambato; in scattered areas around Cuenca in the south-central highlands; and to the north of Loja, where the Saraguro people live. In the southeastern lowlands are the large Shuar and Achuar groups, related to similar groups across the border in Peru; the lowland Quichua speakers, made up of several groups, occupy much of the central Amazon lowlands, along with the Huaorani in the area between the Napo and Curaray rivers and the dwindling Záparo group near the Conambo River. In the northern Oriente are the small groups of Cofán and Siona-Secoya. The Costa, from north to south, includes small groups: the Awa (Kwaiker), Chachi (Cayapa), and Tsáchila (Colorado). Other, much smaller groups of Indian-language speakers reside throughout the country.

The descendants of enslaved Africans (sometimes called Afro-Ecuadorans) live mainly in the northwest coastal region of Esmeraldas and in the Chota River valley in the northern highlands. Both communities have distinctive cultures and are well-defined ethnic groups.

Languages

Spanish is Ecuador’s official language of business and government, although there are dialectal differences between Sierra and Costa Spanish; Sierra Spanish has been influenced by Quichua. Quichua and Shuar (both of which are official intercultural languages) as well as other ancestral languages are spoken by the country’s indigenous people. More than 10 Indian languages exist in Ecuador, and several of these will likely persist as mother tongues. Most Indian males are bilingual, and women are increasingly becoming bilingual as well. The concepts of bilingualism and bilingual or bicultural education are becoming increasingly important.

Religion

Ecuador is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic. The Roman Catholic Church plays a significant role in education and social services and influences the selection of significant places for festivals and pilgrimage sites, such as Quinche in the north and Biblián in the south. Protestantism continues to grow rapidly, particularly among the disadvantaged; the largest groups are the non-Pentecostal Evangelicals and the Pentecostals. There is also a sizable Mormon congregation. Quito, Ambato, and Guayaquil have been urban centres of Protestant activity, and many of the Indians of the Sierra and Oriente have also converted. Many highlanders are practicing Catholics, and religion plays an important part in daily life. In Carchi, Azuay, and Loja provinces in the Sierra and in Manabí province in the Costa, there has been more reluctance to accept Protestant conversion. A small Jewish population is concentrated in Quito, and there are also some Bahāʿī adherents.

Art & Culture of Ecuador

The arts

Ecuador has a rich tradition of folk art. Quito was a colonial centre of wood carving and painting, and artisans still produce replicas of the masterpieces of the Quito school. Certain mestizo and indigenous communities have specialized in particular crafts, such as agave-fibre bags near Riobamba and Salcedo; wood carving at Ibarra; leatherwork at Cotacachi; woolen tapestries at Otavalo, Doctor Miguel Egas, and Salasaca; carpets at Guano; and Panama hats at Monte Cristi and near Cuenca. Folk music is equally rich, including the well-known yumbo and sanjuanito from the highlands (rhythmic and repetitive musical forms associated with festival dancing) and the slow, sad pasillo from the lowlands, as well as the varying local African and Indian (Amazonian, highland, and coastal) traditions. A revival of interest in folklore among the urban populations has led to the creation of folkloric dance troupes. Modern music is influenced by Colombian cumbia (a loping, rolling rhythm often classified as salsa and played in 4/4 time with a heavy emphasis on the first note of the measure and the second and third beats accentuated) and Caribbean salsa (a group of syncopated Latin rhythmic styles using the clave beat; it is based on the Cuban son) and recorded by Ecuadoran groups with local themes.

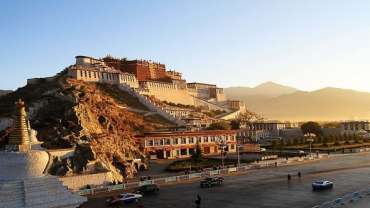

Folk architecture is constructed with a variety of materials, including bamboo, adobe, rammed earth, wattle and daub, and wood; modern architects have come to realize the continued potential of these traditions. Ecuador’s architectural monuments include the large tolas (pre-Inca ramp mounds) of the northern highlands, such as those protected at the Cochasquí archaeological park; the Inca stone walls of Ingapirca near Cañar; the great colonial churches of Quito—especially San Francisco and La Compañía—with their paintings, statuary, and gilt wood carving; and the entire old urban centre of Quito, which in 1978 was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, as was that of Cuenca in 1999.

More-contemporary art is represented by one of the best-known international figures, painter Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919–99); of mestizo-Indian parentage, he earned an international reputation depicting the social ills of his society. Jorge Icaza’s indigenist novel Huasipungo (1934), which depicts the plight of Andean Indians in a feudal society, also received international attention. Many novelists have come from the coast, including those of the so-called Guayaquil group, who explored life among the region’s montuvio population (people of mixed Indian, African, and European heritage) in a spirit of social realism; other novelists of note include Luis Martínez, Demetrio Aguilera Malta, Joaquin Gallegos Lara, Enrique Gil Gilbert, Alfredo Pareja Diez-Canseco, and José de la Cuadra. Cuenca is noted for its poets, including Jorge Carrera Andrade and César Dávila Andrade. Books are published by both private and public presses, and Ecuadorans have access to large book fairs and well-stocked bookstores.

Cultural milieu

Ecuador is a country of great ethnic diversity and great contrasts of wealth and poverty (see People). People identify more with their region or village than with the country as a whole, although the government has attempted to nourish a sense of pan-Ecuadoran national identity. At a minimum, the country may be divided into a dozen major folk-cultural regions: norteño mestizo, northern Quechua, central highland mestizo, Quiteño urban, central Quechua, Cuencano mestizo, Lojano mestizo, southern Quechua, Esmeraldeño blacks, coastal mestizo-mulatto, Shuar (Jivaro), and Amazonian Quechua. Numerous smaller or more-localized cultures also exist, and there are two culturally mixed areas in Santo Domingo de los Colorados and the northeastern Oriente. The most prominent and representative groups are the central highland mestizos and the coastal mestizo-mulatto mixed culture; both increasingly find their identities linked with the cities and urban cultures of Quito and Guayaquil, respectively.

Daily life and social customs

Most Ecuadorans place great emphasis on the family, including fictive kinship, which is established by the choice of godparents at baptism. Apart from baptism, important occasions in the life cycle include the quinceañera (the 15th birthday of girls), marriage, and funerals. Many Ecuadorans make pilgrimages or dedicate themselves to the service of a particular saint. During the year, numerous religious and secular festivals provide opportunities for parades, special food, and music and dance.

Some of the more important ones are not national but, rather, are associated with local urban or regional traditions, such as the holidays of Quito (December 1–6; Founder’s Day [December 6] celebrated throughout the week with festivals, parades, and sporting events), Guayaquil (October 9; Guayaquil state’s Independence Day [from Spain, 1820]), and Cuenca (November 3; Cuenca state’s Independence Day [from Spain, 1820]), as well as the Yamor festival (a rite in early September at the end of the harvest honouring corn, a symbol of generosity and fertility) in Otavalo. Often holidays are associated with particular cities, such as the Day of the Dead (November 2) in Ambato or Carnival (celebrated before Lent) in Guaranda, and they attract people from various parts of the country. The Festival of San Juan Bautista is especially important for the Indian populations of the northern highlands, for whom the holiday occasions dance and music. Many holidays are associated with particular foods or drinks, and music, live or recorded, is a part of most celebrations.

Easter is an opportunity to eat fanesca, a soup that is virtually the Ecuadoran national dish. The soup—made of onions, peanuts, fish, rice, squash, broad beans, chochos (lupine), corn (maize), lentils, beans, peas, and melloco (a highland tuber)—combines highland and lowland ingredients and is a culinary model of the union of diverse national characteristics. Chili sauce (ají) is part of most meals. Empanadas are deep-fried and stuffed savoury pastries. Typical of the coast is seviche, made with shrimp or shellfish or even mushrooms pickled with lemon juice, cilantro (coriander), and onions. Coastal cuisine also includes deep-fried plantains and various rice dishes. Highland cuisine is based on staples such as quinoa and barley soups and on more-complex soups and stews that mix combinations of corn, potatoes, oca, quinoa, melloco (a tuber), beans, barley, broad beans, and squash. Restaurants in Quito, Guayaquil, and other large cities offer a variety of ethnic cuisines, as well as food that has been popularized by U.S. franchises.

Nightlife remains limited in the smaller towns, where the young middle class may be cruising in cars or motorcycles and hanging out at local restaurants or plazas. Young people of different sexes may mix in groups, but dating is relatively rare, and there is little in the way of a singles scene. A nightlife has developed in Quito and Guayaquil since the 1980s, however, focusing on discos, restaurants, and bars. Musical tastes range from the traditional pasillos and cumbia to 1970s disco hits and hip-hop music; all styles may be played in a single evening. Jazz, poetry readings, folk music, and arena rock concerts are also entertainment options, often drawing international tourists.

Each of Ecuador’s Indian communities has a traditional style of dress. Highland Indian males may wear coloured ponchos—for instance, blue in the Otavalo area and red in western Chimborazo. Traditional footwear is sandals, and a variety of traditional hats may be worn; in some locations hair is still worn long by both men and women, gathered in a ponytail. Highland Indian women may wear embroidered blouses, wrapped skirts of woolen cloth, shawls attached with a pin in front, sandals, and locally produced hats or headgear. Lowlanders wear loose-fitting clothing, including guayabera shirts for men. Both highlanders and lowlanders wear business suits on formal occasions, while young people wear international fashions such as jeans and khakis.

Heritage Festivities - Traditional Festivals: A tour of the cultural manifestations of the four worlds in Ecuador

Traditional festivals in Ecuador can be identified as ancestral or indigenous, and traditional mestizo. Among the first are the festivities of the equinoxes and solstices, which were inserted into the Catholic calendar during the colonial period, such as the Carnival festivities prior to Lent, the Inti Raymi festival, which is celebrated in the Andes world, the same which starts with the Corpus Christi festival, the San Juan and San Pedro fiestas, in the north of Pichincha; and, the festival of Jora and Yamor in Imbabura.

While traditional mestizo festivities, for its symbolic richness and its historical-cultural implications, we can highlight: the Diablada de Píllaro, the Carnival, Holy Week, the pilgrimage of the Virgen del Cisne in Loja, the Romería a la Vírgen del Quinche, the feast of the Black Mama in homage to the Virgen de las Mercedes in Latacunga, the Rodeos Montubios of the provinces of Guayas and Los Ríos in the Costa World, the Pass of the Child in Cuenca, and the Old Years throughout the country , where popular creativity is evident in the construction of ingenious cardboard and paper dolls, which at midnight on December 31 are burned among multiple rituals, joy and joy, to receive the New Year with promises and good omens.