Visit Macedonia - the undiscovered paradise!

Macedonia is a veritable treasury of cultural heritage. Macedonia treasures a large number of cultural and historical monuments: churches, monasteries, icons, archaeological sites, mosques, old books, and other artefacts. The first Slavic alphabet and literature also have their roots here. Many internationally recognized events are held in Macedonia: Ohrid Summer Festival, Struga Poetry Evenings, Ohrid Balkan Festival, Galicnik Wedding. National folklore and traditional arts and crafts are still cherished. The finely embroidered national costumes, the numerous old crafts shops have played an important part in preserving the tradition.

The Republic of Macedonia is a paradise of sun, mountains, rivers and lakes that offer the visitor a complete change from the stress and routine of everyday life. If you visit Macedonia from April to October, most places in Macedonia have an ideal climate that is perfect for relaxing & enjoying the beautiful nature of mountains and lakes, while the rest of the year you have the clear Macedonian mountains and ski resorts.

While easily accessible from all points abroad, and boasting all the amenities of the Western world, Macedonia remains one of Europe’s last great undiscovered countries: a natural paradise of mountains, lakes and rivers, where life moves to a different rhythm, amidst the sprawling grandeur of rich historical ruins and idyllic villages that have remained practically unchanged for centuries.

History of Macedonia

The ancient world

The Macedonian region has been the site of human habitation for millennia. There is archaeological evidence that the Old European (Neolithic) civilization flourished there between 7000 and 3500 BCE. Seminomadic peoples speaking languages of the Indo-European family then moved into the Balkan Peninsula. During the 1st millennium BCE the Macedonian region was populated by a mixture of peoples—Dacians, Thracians, Illyrians, Celts, and Greeks. Although Macedonia is most closely identified historically with the kingdom of Philip II of Macedon in the middle of the 4th century BCE and the subsequent expansion of that empire by his son Alexander III (the Great), none of the states established in that era was very durable. Until the arrival of the Romans, the pattern of politics was a shifting succession of contending city-states and chiefdoms that occasionally integrated into ephemeral empires. Nevertheless, this period is important in understanding the present-day region, as both Greeks and Albanians base their claims to be indigenous inhabitants of it on the achievements of the Macedonian and Illyrian states.

At the end of the 3rd century BCE, the Romans began to expand into the Balkan Peninsula in search of metal ores, slaves, and agricultural produce. The Illyrians were finally subdued in 9 CE (their lands becoming the province of Illyricum), and the north and east of Macedonia were incorporated into the province of Moesia in 29 CE. A substantial number of sites bear witness today to the power of Rome, especially Heraclea Lyncestis (modern Bitola) and Stobi (south of Veles on the Vardar River). The name Skopje is Roman in origin (Scupi). Many roads still follow courses laid down by the Romans.

Beginning in the 3rd century, the defenses of the Roman Empire in the Balkans were probed by Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Avars, and other seminomadic peoples. Although the region was nominally a part of the Eastern Empire, control from Constantinople became more and more intermittent. By the mid-6th century Slavic tribes had begun to settle in Macedonia, and from the 7th to the 13th century the entire region was little more than a system of military marches governed uneasily by the Byzantine state through alliances with local princes.

The medieval states

In the medieval period the foundations were laid for modern competing claims for control over Macedonia. During the 9th century the Eastern tradition of Christianity was consolidated in the area. The mission to the Slavs has come to be associated with Saints Cyril and Methodius, whose great achievement was the devising of an alphabet based on Greek letters and adapted to the phonetic peculiarities of the Slavonic tongue. In its later development as the Cyrillic alphabet, this came to be a distinctive cultural feature uniting several of the Slavic peoples.

Although the central purpose of the missionaries was to preach the Gospel to the Slavs in the vernacular, their ecclesiastical connection with the Greek culture of Constantinople remained a powerful lever to be worked vigorously during the struggle for Macedonia in the 19th century. About three-fourths of the inhabitants of the present-day Republic of North Macedonia have a Macedonian national identity. They are Slavic-speaking descendants of the Slavic tribes who have lived in the area since the 6th century. The long association of the area with the Greek-speaking Byzantine state, and the Greek claim to continuity with the ancient Macedonian empire of Alexander the Great, led the Greek state to claim that “Macedonia was, is, and always will be Greek.” Since the independence of the Republic of Macedonia in 1991, Greece on these grounds attempted to block the international recognition of the Republic of Macedonia by its constitutional name and to deny the Macedonians of the Republic of Macedonia and Greece the right to identify themselves as Macedonians.

What is less clear is the history of the emergence of a Macedonian national identity from a more general identity as Slavic-speaking Orthodox Christians as well as from a Bulgarian national identity, the latter of which developed before a Macedonian identity did. Among the short-lived states jostling for position with Byzantium were two that modern Bulgarians claim give them a special stake in Macedonia. Under the reign of Simeon I (893–927), Bulgaria emerged briefly as the dominant power in the peninsula, extending its control from the Black Sea to the Adriatic. Following a revolt of the western provinces, this first Bulgarian empire fell apart, but it was partially reintegrated by Samuel (reigned 976–1014), who set up his own capital in Ohrid (not the traditional Bulgarian capital of Preslav [now known as Veliki Preslav]) and also established a patriarchate there. Although the Byzantine state reasserted its authority after 1018, a second Bulgarian empire raised its head in 1185; this included northern and central Macedonia and lasted until the mid-14th century.

During the second half of the 12th century, a more significant rival to Byzantine power in the Balkans emerged in the Serbian Nemanjić dynasty. Stefan Nemanja became veliki župan, or “grand chieftain,” of Raška in 1169, and his successors created a state that under Stefan Dušan (reigned 1331–55) incorporated Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, all of modern Albania and Montenegro, a substantial part of Bosnia, and Serbia as far north as the Danube. Although the cultural heart of the empire was Raška (the area around modern Novi Pazar) and Kosovo, as the large number of medieval Orthodox churches in those regions bear witness, Stefan Dušan was crowned emperor in Skopje in 1346. Within half a century after his death, the Nemanjić state was eclipsed by the expanding Ottoman Empire; nevertheless, it is to this golden age that Serbs today trace their own claims to Macedonia.

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire originated in a small emirate established in the second half of the 13th century in northwestern Anatolia. By 1354 it had gained a toehold in Europe, and by 1362 Adrianople (modern Edirne, Turkey) had fallen. From this base the power of this Turkish and Islamic state steadily expanded. From a military point of view, the most significant defeat of the Serbian states took place in the Battle of the Maritsa River at Chernomen in 1371, but it is the defeat in 1389 of a combined army of Serbs, Albanians, and Hungarians under Lazar at the Battle of Kosovo that has been preserved in legend as symbolizing the subordination of the Balkan Slavs to the “Ottoman yoke.” Constantinople itself did not fall to the Ottoman Turks until 1453, but by the end of the 14th century the Macedonian region had been incorporated into the Ottoman Empire. Thus began what was in many respects the most stable period of Macedonian history, lasting until the Turks were ejected from the region in 1913.

Half a millennium of contact with Turkey had a profound impact on language, food, and many other aspects of daily life in Macedonia. Within the empire, administrators, soldiers, merchants, and artisans moved in pursuit of their professions. Where war, famine, or disease left regions underpopulated, settlers were moved in from elsewhere with no regard for any link between ethnicity and territory. By the system known as devşirme (the notorious “blood tax”), numbers of Christian children were periodically recruited into the Turkish army and administration, where they were Islamized and assigned to wherever their services were required. For all these reasons, many Balkan towns acquired a cosmopolitan atmosphere. This was particularly the case in Macedonia during the 19th century, when, as the Serbian, Greek, and Bulgarian states began to assert their independence, many who had become associated with Turkish rule moved into lands still held by the Sublime Porte.

The economic legacy of Turkish rule is also important. During the expansionist phase of the empire, Turkish feudalism consisted principally of the timar system of “tax farming,” whereby local officeholders raised revenue or supported troops in the sultan’s name but were not landowners. As the distinctively military aspects of the Ottoman order declined after the 18th century, these privileges were gradually transformed in some areas into the çiftlik system, which more closely resembled proprietorship over land. This process involved the severing of the peasantry from their traditional rights on the land and a corresponding creation of large estates farmed on a commercial basis. The çiftlik thus yielded the paradox of a population that was heavily influenced by Ottoman culture yet bound into an increasingly oppressive economic subordination to Turkish landlords.

People of Macedonia

Ethnic groups

The population of the Republic of North Macedonia is diverse. At the beginning of the 21st century, nearly two-thirds of the population identified themselves as Macedonians. Macedonians generally trace their descent to the Slavic tribes that moved into the region between the 6th and 8th centuries CE. Albanians are the largest and most-important minority in the Republic of North Macedonia. According to the 2002 census, they made up about one-fourth of the population.

The Albanians—most of whom trace their descent to the ancient Illyrians—are concentrated in the northwestern part of the country, near the borders with Albania and Kosovo. Albanians form majorities in some 16 of North Macedonia’s 80 municipalities. Other, much smaller minorities (constituting less than 5 percent of the population each) include the Turks, Roma, Serbs, Bosniaks, and Vlachs (Aromani). The Turkish minority is mostly scattered across central and western North Macedonia, a legacy of the 500-year rule of the Ottoman Empire. The majority of Vlachs, who speak a language closely related to Romanian, live in the old mountain city of Kruševo.

Language

The Macedonian language is very closely related to Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian and is written in the Cyrillic script. When Serbian rule replaced that of the Ottoman Turks in 1913, the Serbs officially denied Macedonian linguistic distinctness and treated the Macedonian language as a dialect of Serbo-Croatian. The Macedonian language was not officially recognized until the establishment of Macedonia as a constituent republic of communist Yugoslavia in 1945.

Religion

Religious affiliation is a particularly important subject in North Macedonia because it is so closely tied to ethnic and national identity. With the exception of Bosniaks, the majority of Slavic speakers living in the region of Macedonia are Orthodox Christian. Macedonians, Serbs, and Bulgarians, however, have established their own autocephalous Orthodox churches in an effort to assert the legitimacy of their national identities. The majority Greeks in the region of Greek Macedonia, who also identify themselves as Macedonians, are Orthodox as well, but they belong to the Greek Orthodox Church. Turks and the great majority of both Albanians and Roma are Muslims. Altogether, about one-third of the population is of the Islamic faith.

Cultural Life of Macedonia

Daily life and social customs

As a result of the long presence of the Ottoman Turks in the region, the traditional cuisine of North Macedonia is not only based on Balkan and Mediterranean fare but also flavoured by Turkish influences. Among the country’s dishes of Turkish origin are kebapcinja (grilled beef kebabs) and the burek, a flaky pastry often stuffed with cheese, meat, or spinach. Macedonians also enjoy other foods that are common throughout the Balkans, including taratur (yogurt with shredded cucumber) and baklava. Macedonian specialties include ajvar (a sauce made from sweet red peppers), tavce gravce (baked beans), shopska salata (a salad combining sliced cucumbers, onions, and tomatoes with soft white cheese), and selsko meso (pork chops and mushrooms in brown gravy).

In addition to Orthodox Christian and Islamic religious holidays, a number of holidays tied to the country’s history are celebrated in North Macedonia, including Independence Day (September 8), marking the day in 1991 when Macedonians voted for independence from federated Yugoslavia.

The arts

Despite the refusal of Macedonia’s Serbian rulers to recognize Macedonian as a language, progress was made toward the foundation of a national language and literature in the early 20th century, especially by Krste P. Misirkov in his Za Makedonskite raboti (1903; “In Favour of Macedonian Literary Works”) and in the literary periodical Vardar (established 1905). These efforts were continued during the interval between World War I and World War II, most notably by the poet Kosta Racin. After World War II, Macedonia—freed to write and publish in its own language—produced such literary figures as poets Aco Šopov, Slavko Janevski, Blae Koneski, and Gane Todorovski. Janevski also authored the first Macedonian novel, Selo zad sedumte jaseni (1952; “The Village Beyond the Seven Ash Trees”), and a cycle of six novels dealing with Macedonian history. After World War II, Macedonian theatre was invigorated by a wave of new dramatists that included Kole Čašule, Tome Arsovski, and Goran Stefanovski. Among the best-known fiction writers of prose are Živko Čingo, Vlada Urošević, and Jovan Pavlovski. (See Macedonian literature).

The popular culture of North Macedonia is a fascinating blend of local tradition and imported influence. Folk music and folk dancing are still popular, and rock and pop music are ubiquitous. Icon painting and wood carving both have long histories in North Macedonia. Motion picture making in North Macedonia dates to the early 20th-century efforts of brothers Milton and Janaki Manaki and includes Before the Rain (1994), which was directed by Milcho Manchevski and was nominated for an Academy Award for best foreign-language film.

Cultural institutions

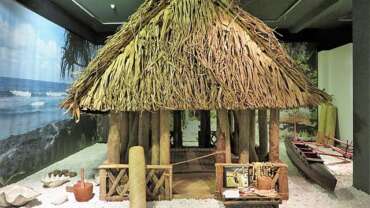

Located in Ohrid, the National Museum features an archaeological collection dating from prehistoric times. Ohrid itself is one of the oldest human settlements in Europe, and the natural and cultural heritage of the Ohrid region was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980. Also of note are the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje and the Museum of the City of Skopje.

Throughout the country, annual festivals are held, including the Skopje Jazz Festival, the Balkan Festival of Folk Songs and Dances in Ohrid, the Ohrid Summer Festival, and the pre-Lenten Carnival in Strumica. An international poetry festival is held annually in the lakeside resort of Struga.

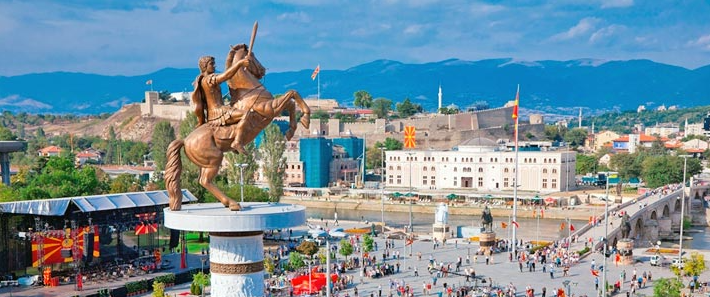

About Skopje, Macedonian capital

Skopje is Macedonia’s largest city and therefore, chosen to be the capital of Macedonia. Skopje urban area extends across the Skopje valley for approximately 30 kilometres (18.75 mi) in width and comprises 10 municipalities. According to the 2002 census, the urban municipalities of Skopje had a population of 506.926 or slightly more than a quarter of the population of Macedonia. Skopje metropolitan population approximates 700,000 inhabitants. Skopje is situated in the Skopje valley (north-western part of Macedonia), on the both banks in the river Vardar river, at an altitude of 255 meters above the sea level.