Myanmar - Be Enchanted!

Myanmar is one of the last countries of Asia to be revealed to the travelling world. Located between India, China and Thailand, the people of this enchanted land have developed a culture which has endured invasion and change by absorbing and taking the best from those around them and creating their own style and flair.

Visitors to Myanmar will find there is much to discover and experience – from pristine natural regions to golden pagodas to relics from an ancient past.

With more than 130 distinct ethnic groups, Myanmar has a wealth of different cultures, each with its own set of traditions: from cuisine and dress to celebration, faith and occupation. Visitors are welcome to discover Myanmar’s diversity of traditions and are urged to do so responsibly to help foster cultural understanding and create lasting bonds.

History of Myanmar

Myanmar has been a nexus of cultural and material exchange for thousands of years. The country’s coasts and river valleys have been inhabited since prehistoric times, and during most of the 1st millennium CE the overland trade route between China and India passed through Myanmar’s borders. Merchant ships from India, Sri Lanka, and even farther west converged on its ports, some of which also were the termini of the portage routes from the Gulf of Thailand across the narrow Isthmus of Kra on the Malay Peninsula. Thus, Myanmar has long served as the western gateway of mainland Southeast Asia.

The Indian merchants brought with them not only precious cargoes but also their religious, political, and legal ideas; within just a few decades after the first of these merchants arrived, Indian cultural traditions had remolded indigenous society, thought, and arts and crafts. Yet important components of Myanmar’s local ways were retained, in synthesis with Indian culture. Surrounded on three sides by mountains and on the fourth by the sea, Myanmar always has been somewhat isolated; as a consequence, its cultures and peoples have remained distinct in spite of the many Indian influences and in spite of its close affinity with the cultures of the other countries of Southeast Asia.

Myanmar was one of the first areas in Southeast Asia to receive Buddhism, and by the 11th century it had become the centre of the Theravada Buddhist practice. The religion was patronized by the country’s leadership, and it became the ideological foundation of the Myanmar state that blossomed at Pagan on the dry central plains.

The origins of civilization in Myanmar

The first human settlers in Myanmar appeared in the central plain some 11,000 years ago. Little is known of these people except that they were a Paleolithic culture, using stone and fossilized-wood tools that have been labeled Anyathian, from Anyatha (another term for Upper Burma). A discovery in 1969, by workers from the government’s Department of Archaeology, of some cave paintings and stone tools in the eastern part of Shan state shows that that area too had Paleolithic as well as early Neolithic (about 10,000 years ago) settlements, both of which bore similarities to the Hoabinhian culture, which was widespread in the rest of Southeast Asia from about 13,000 to about 4,000 BCE. Crude shards and ring stones found at the site appear to have been attached to stonecutting tools to make them more suitable for digging. The woodcutting tools in the find probably were used to clear patches of forest for cultivation, which would indicate that the shift from gathering to agriculture had already begun.

The Pyu state

Between the 1st century BCE and the 9th century CE, speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages known as the Pyu established city-kingdoms in Myanmar at Binnaka, Mongamo, Shri Kshetra, and Halingyi. At the time, a long-standing trade route between China and India passed through northern Myanmar and then across the Chindwin River valley to the west. In CE 97 and 121, Roman embassies to China chose this overland route through Myanmar for their journey. The Pyu, however, provided an alternative route down the Irrawaddy to their capital city, Shri Kshetra, at the northern edge of the delta. From there, the route extended by sea westward to India and eastward to insular Southeast Asia, where the China trade connected with the portage routes on the peninsula and with maritime routes within the archipelago. Chinese historical records noted that the Pyu claimed sovereignty over 18 kingdoms, many of them in the southern portions of Myanmar.

The same Chinese records emphasized the humane nature of Pyu government and the elegance and grace of Pyu life. Fetters, chains, and prisons were evidently unknown, and punishment for criminals was a few strokes with a whip. The men, dressed in blue, wore gold ornaments on their hats, and the women wore jewels in their hair. The Pyu lived in houses built of timber and roofed with tiles of lead and tin; they used golden knives and utensils and were surrounded by art objects of gold, green glass, jade, and crystal. Parts of the city walls, the palace, and the monasteries were built of glazed brick. The Pyu also appear to have been Buddhists of the Sarvastivada school. Their architects may have developed the vaulted temple, which later found its greatest expression at Pagan during its golden age, from the 11th to the 14th century. Pyu sons and daughters were disciplined and educated in monasteries or convents as novices. In the 7th century the Pyu shifted their capital northward to Halingyi in the dry zone, leaving Shri Kshetra as a secondary centre to oversee trade.

The Mon

To the south of the Pyu lived the Mon, who were speakers of an Austroasiatic language. The Mon were closely related to the Khmer, who lived to the east of the Mon in what is now Cambodia. The capital of the Mon probably was the port of Thaton, which was located northwest of the mouth of the Salween River and not far from the portage routes of the Malay Peninsula; through this window to the sea the Mon saw India, in its full glory, under the Gupta dynasty (early 4th to late 6th century CE). Earlier, in the 3rd century BCE, the great Mauryan emperor Ashoka apparently had sent a mission of Buddhist monks to a place called Suvarnabhumi (the Golden Land), which is now thought to have been in the Mon region of the Isthmus of Kra. The ancient monastic settlement of Kelasa, situated near Thaton in southern Myanmar and claimed by Burmese and Mon chronicles to have been founded by Ashoka’s missionaries, was mentioned in early Sinhalese records as being represented at a great religious ceremony held in Sri Lanka in the 2nd century BCE.

With the expansion of Indian commerce in Southeast Asia between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, Thaton’s prosperity and importance increased. Indian merchants and seamen went to Thaton as traders rather than as conquerors or colonists. The number of Indians was never great, and their settlements were of a commercial, not military, nature. As a result, Indian culture was readily accepted by the Mon.

However, the Mon culture was not displaced by Indian ways; the Mon blended the old with the new. They integrated many of their own beliefs into those of Theravada Buddhism, which arrived in Southeast Asia already replete with local South Asian beliefs. The power and prestige of the Mon kingship were enhanced by the notions of kingship found in India. The Mon developed a new art of sculpture by blending indigenous traditions with Gupta conventions of iconography. They built stupas (Buddhist ceremonial mounds) according to Indian models, which were adapted to Mon aesthetic tastes. The Mon subsequently became one of the most culturally advanced peoples in Southeast Asia. They assumed the role of teachers to their neighbours, spreading Theravada Buddhism and their new culture over the entire region.

The Mon centre eventually shifted to Bago (Pegu), located on the Bago River, about 50 miles (80 km) northeast of present-day Yangon (Rangoon). From there the Mon were able to control the trade of southern Myanmar.

The kingdom of Pagan (849–c. 1300)

The advent of the Burmans at Pagan

Another group of Tibeto-Burman speakers, the Burmans, also had become established in the northern dry zone. They were centred on the small settlement of Pagan on the Irrawaddy River. By the mid-9th century, Pagan had emerged as the capital of a powerful kingdom that would unify Myanmar and inaugurate the Burman domination of the country that has continued to the present day.

During the 8th and 9th centuries the kingdom of Nanzhao became the dominant power in southwestern China; it was populated by speakers of Lolo (or Yi), a Tibeto-Burman language. Nanzhao mounted a series of raids on the cities of mainland Southeast Asia in the early decades of the 9th century and even captured Hanoi in 861. The Mon and Khmer cities held firm, but the Pyu capital of Halingyi fell. The Burmans moved into this political vacuum, establishing Pagan as their capital city in 849.

By that time the Mon apparently had become supreme in southern Myanmar. They may have occupied the whole of the region and controlled the port of Pathein (Bassein) in the west and the city of Bago in the centre. They could have stepped into the void caused by the destruction of the Pyu kingdom, but their power was linked to the trade of southern Myanmar and not with the agrarian-based economy of northern Myanmar.

The unification of Myanmar

Nanzhao acted as a buffer against Chinese power to the north and allowed the infant Burman kingdom to grow. The Burmans learned much from the Pyu, but they were still cut off from the trade revenues of southern Myanmar. Theravada Buddhism had disappeared from India, and in its place were Mahayana Buddhism and a resurgent Hinduism.

People of Myanmar

Ethnic groups

Myanmar is a country of great ethnic diversity. The Burmans, who form the largest group, account for more than half of the population. They are concentrated in the Irrawaddy River valley and in the coastal strips, with an original homeland in the central dry zone.

The Karen are the only hill people who have settled in significant numbers in the plains. Constituting about one-tenth of the population, they are the second largest ethnic group in Myanmar. They are found in the deltas among the Burmans, in the Bago Mountains, and along both sides of the lower Salween River. The Kayah, who live on the southern edge of the Shan Plateau, were once known as the Red Karen, or Karenni, apparently for their red robes. Although ethnically and linguistically Karen, they tend to maintain their own identity and hereditary leadership.

The Shan of the Shan Plateau have little ethnolinguistic affinity with the Burmans, and, although historically led by hereditary rulers, their society was less elaborately structured than that of the plains peoples. The Shan represent a small but significant portion of the country’s population.

The Irrawaddy and Sittang deltas were once peopled by the Mon, who likely entered the country more than two millennia ago from their kingdoms in the Chao Phraya River valley in Thailand. The Mon were conquered in the 11th century by the Burmans, and by the end of the 18th century they had largely been incorporated into Burman society—by intermarriage as well as by suppression. A sizable number still remain in the Sittang valley and in the Tenasserim region; although they continue to call themselves Mon, most have assimilated virtually imperceptibly into Burman culture and no longer speak their original language.

Numerous small ethnic groups, most of which inhabit the upland regions, together account for roughly one-fifth of Myanmar’s population. In the western hills and the Chindwin River valley are various groups called by the comprehensive name of Chin. The upper Irrawaddy valley and the northern hills are occupied by groups under the comprehensive name of Kachin. These peoples long have had an association with the Burmans.

The ethnographic complexity of the highlands occasionally leads to misgroupings of some of the smaller communities with their more prominent neighbours. For example, the Wa and the Palaung of the Shan Plateau are often grouped with the larger—but ethnically and linguistically distinct—Shan community. Similarly, the Naga on the Myanmar side of the frontier with India sometimes are mistakenly placed with the Chin, and the Muhso (a Lahu people) in northeastern Myanmar are grouped with the Kachin.

During the period of British colonial rule, there were sizable communities of South Asians and Chinese, but many of these people left at the outbreak of World War II. A second, but forced, exodus took place in 1963, when commerce and industry were nationalized. In the early 21st century the Chinese constituted a small but notable portion of Myanmar’s people.

Languages

Many indigenous languages—as distinct from mere dialects—are spoken in Myanmar. The official language is Burmese, spoken by the people of the plains and, as a second language, by most people of the hills. During the colonial period, English became the official language, but Burmese continued as the primary language in all other settings. Both English and Burmese were compulsory subjects in schools and colleges. Burmese, Chinese, and Hindi were the languages of commerce. After independence English ceased to be the official language, and after the military coup of 1962 it lost its importance in schools and colleges; an elementary knowledge of English, however, is still required, and its instruction is again being encouraged.

The local languages of Myanmar belong to three language families. Burmese and most of the other languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman subfamily of Sino-Tibetan languages. The Shan language belongs to the Tai family. Languages spoken by the Mon of southern Myanmar and by the Wa and Palaung of the Shan Plateau are members of the Mon-Khmer subfamily of Austroasiatic languages.

Speakers of Burmese and Mon historically have lived in the plains, while speakers of a unique dialect of Burmese (that perhaps retains some archaic features of pronunciation) have occupied the Rakhine and Tenasserim coastal plains. The hills were inhabited by those speaking Shan, Kachin, Chin, and numerous other languages. In the plains the ancient division between northern and southern Myanmar (Upper Burma and Lower Burma, respectively) was based not only on geographic differences but also on a linguistic one. The Mon (now a small minority) lived in southern Myanmar, while the majority Burman population lived in the northern dry zone.

Until colonial times only Burmese, Mon, Shan, and the languages of the ancient Pyu kingdom of northern Myanmar were written. Writing systems for the languages of the Karen, Kachin, and Chin peoples were developed later.

Religion

Although Myanmar has no official religion, nearly nine-tenths of the population follows Theravada Buddhism. The vast majority of Burmans and Shan are Buddhist. There is, however, a significant Protestant Christian minority, concentrated primarily among the Karen, Kachin, and Chin communities. Many of the other hill peoples practice local religions, and even those who adhere to world religions typically incorporate local elements to some degree. Muslims, mostly Burman, and Hindus are among the smallest religious minorities.

Settlement patterns

Myanmar is a land of villages. Except for a few large cities—notably Yangon, Mandalay, and Mawlamyine (Moulmein)—the towns essentially are large villages. Although the hill peoples generally practice shifting agriculture (called taungya in Burmese), most have settled in upland villages at some distance from the fields. On the Shan Plateau and in the neighbouring river valleys, the fields adjoin the villages. Older villages are circular in shape, but along the banks of the delta streams and along railways the villages are rectangular. Houses are built of timber and bamboo, the roofs being thatched or tiled. In the past, houses typically were built on piles, the original purpose being protection from wild animals or floods. The style persists in many villages, especially those on the hills, and farm animals are kept under the houses at night. In small towns the piles have been replaced by a supporting brick structure with concrete flooring, with the upper story still being made of timber. Houses entirely of brick were few in number before the mid-20th century, but later many sprang up in Yangon, Mandalay, and larger towns on the rubble of buildings destroyed during World War II. Life in villages is in some respects communal because of custom, the influence of Buddhism, and the redistributive and reciprocal nature of agrarian society.

Art & Culture of Myanmar

Arts of Myanmar

Art of Myanmar refers to visual art created in Myanmar (Burma). From the 1400s CE, artists have been creating paintings and sculptures that reflect the Burmese culture. Burmese artists have been subjected to government interference and censorship, hindering the development of art in Myanmar. Burmese art reflects the central Buddhist elements including the mudra, Jataka tales, the pagoda, and Bodhisattva.

Art of the Shan Period

Art historians do not have an agreed-upon definition of Shan art. It is believed to have originated between 1550 and 1772 CE, which was around the time that the two kingdoms of Lanna and Lan Xang were both under the support of the Burmese.

Many pieces of Shan artwork depict a Buddha in a seated position, with his right hand pointed towards the Earth; this position is commonly known as the Maravijaya Posture. In Buddhism, the Maravijaya pose represents Buddha calling the Earth Goddess to witness Gautama Shakyamuni’s victory over Mara.

Sculptures made in this art style were usually made of bronze and later would be sculpted with wood or in lacquer. Traditional Shan art typically had a Buddha with the characteristic monk’s robes, or adorned with a crown and decorated with various other mediums like putty and glass.

Shan sculptures are distinctive and easily recognizable when looking through the history of Burmese Buddhist art. Shan sculptures are often identified with oval shaped faces, soft smiles, and closed relaxed eyes.

Cultural Life

Buddhism has been a part of Myanmar’s culture since the 1st century CE and has blended with non-Buddhist beliefs. The most conspicuous manifestation of Buddhist culture is the magnificent architecture and sculpture of Myanmar’s many temples and monasteries, notably those at Yangon, Mandalay, and Pagan (Bagan), the site of the ancient kingdom of west-central Myanmar. Myanmar’s culture also is an amalgam of royal and common traditions. Although the dramatic traditions of the Burman court might have appeared to be dying after the elimination of the monarchy in the late 19th century, the tradition survived in a nonroyal context, among the masses. With the growth of nationalism and the regaining of independence, it gathered new strength. The most popular dramatic form is the pwe, which is performed outdoors. There are a variety of pwe genres, including both human and puppet theatre, and most draw subject matter from the Jataka tales—stories of the former lives of the Buddha.

Music and dance are integral to most dramatic forms of the Burmans. The various pwe are accompanied by music of the hsaing waing, a percussive instrumental ensemble with close relatives in neighbouring countries of mainland Southeast Asia. The leading instruments in the hsaing waing include a circle of 21 tuned drums called pat waing, an oboelike hne, a circle of small, horizontally suspended tuned gongs known as kyi waing, and another set of small gongs called maung hsaing. These instruments are supported melodically by other gongs and drums, while a wooden block and a pair of cymbals set the tempo and reinforce the musical structure. Dance styles that are accompanied by hsaing waing are derived in part—and indirectly—from southern India. Much of the Burman dance tradition was adapted from the styles of Thailand and other “Indianized” (or formerly Indianized) states of Southeast Asia, especially during the 18th century.

Softer instruments commonly heard in nontheatrical indoor settings, such as the saung gauk (harp) and pattala (bamboo xylophone), typically accompany singing from a compendium of Burmese songs called Mahagita (“Great Music”). Since colonial times, musicians of Myanmar also have incorporated various instruments of Western origin into their indigenous musical traditions, reworking the instruments’ sound, repertoire, and playing technique to reflect local aesthetics. For example, a significant repertoire of music has been developed for the piano, locally called sandaya, that is stylistically evocative of the circle of tuned drums, the harp, and the xylophone.

Wood carving, lacquerwork, goldwork, silverwork, and the sculpting of Buddhist images and mythological figures also survived during colonial rule; there has been a revival of these and other indigenous art traditions under government patronage. Both the arts of bronze casting among the Burmans and of making bronze drums among the Karen and Shan, however, disappeared. The cinema and rock-based popular music are two international art forms that have been accepted into the cultural life of Myanmar.

Burmese literature is an intimate blend of religious and secular genres. It remained alive throughout the colonial period and, in both verse and prose, has continued to thrive. A later (though not entirely new) development was biography, which has become more popular than fiction. Government-sponsored awards are given annually for the best translation, the best novel, and the best biography.

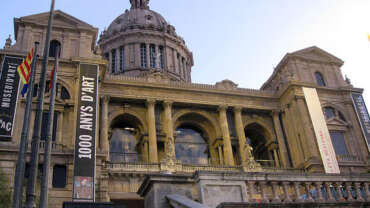

Among Myanmar’s most prominent cultural institutions are the state schools of dance, music, drama, and fine arts at Yangon and Mandalay, as well as the National Museum of Art and Archaeology at Yangon. There also is an archaeological museum at Pagan. A number of other museums focus on state and regional history.

Since 1962 the government has strictly controlled and censored all media. The New Light of Myanmar (published in English and Burmese), which is the most prominent of several daily newspapers, is the official voice of the government. Several underground print newspapers circulate irregularly, and the opposition newspaper BurmaNet News is available electronically, although it is difficult to obtain in Myanmar. The government-operated Myanma TV and Radio Department has television programming in Burmese and Arakanese and radio programming in Burmese, English, and a number of local languages. Some foreign radio services—most notably Radio Free Asia, Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and the Democratic Voice of Burma (an opposition station operated out of Norway by Burmese expatriates)—are an important source of international as well as domestic news. Internet use is highly restricted.

Silver Beaches & Flowing Rivers

Myanmar’s premier coastal resort is Ngapali Beach. It is a picture of paradise: miles of empty white sand beaches lined with tall coconut palms. Resort hotels offer visitors the chance to swim, sail, kayak and feast on lobster and prawn by candlelight as the sun sinks into the Bay of Bengal. The neighbouring town of Thandwe has a large market offering traditional pottery, basketry and woven goods apart from the usual fresh produce and fish. The fishermen who moor their boats at a rocky patch of beach are friendly and happy to show off their catch.

The most recent discovery on the west coast is Ngwe Saung Beach. This 14.5-kilometre stretch of coastline offers pure white sand, an unspoiled backdrop of lush forests, groves of palm trees and a new crop of oceanfront luxury hotels. For visitors who want to be more active, there is a beautiful golf resort, as well as diving, sailing and other water sports. The islands and villages in the vicinity are excellent places to explore for those who want to have a sense of local life.

It is a picture of paradise: miles of empty white sand beaches lined with tall coconut palms. Resort hotels offer visitors the chance to swim, sail, kayak and feast on lobster and prawn by candlelight as the sun sinks into the Bay of Bengal.

Just to the north of Ngwe Saung is Chaungtha Beach. With a wide range of accommodation available at reasonable prices, and with seafood cheap and abundant, it is a long-time favourite among local beachgoers. Hired bullock carts or bicycles can be used to follow pathways that will take visitors past small fishing villages on their way to secluded beaches far from the commotion of the hotel areas.

Travelling by boat offers a great opportunity to sit back, relax and observe the pulse of life along the waterways of Myanmar. Cruises float past timber camps with elephants taking baths at sundown, families camped out to pan for gold, grassy banks with picturesque villages, fishermen pulling in the catch of the day with their nets, and jetties where hawkers sell rice cakes and grilled fish.

One of the great rivers of Asia, the Ayeyarwady is the cultural and economic lifeline of Myanmar. From its headwaters in the Himalaya Mountains, it runs the entire length of the country, passing through thick jungles and towering gorges, and into the very heart of Myanmar’s civilisation, ancient and modern.

The most popular trip on the Ayeyarwady River among visitors is between Mandalay and Bagan. The journey can be done as a no-frills daytrip on a local ferry or as a multi-day excursion on a luxury vessel that stops at notable villages and Buddhist monasteries along the way to provide a real glimpse of riverside lifestyles. For those who cannot resist the lure of the mighty Ayeyarwady, extended luxury trips can be scheduled year-round to travel as far south as Pyay in Bago Division and as far north as Bhamo in Kachin State.

Adventurous travellers can also embark on boat excursions on the untamed Chindwin River, which flows through the wilderness of Sagaing Division, passing the town of Monywa before spilling into the Ayeyarwady between Mandalay and Bagan. The river is navigable by luxury boat from its confluence with the Ayeyarwady all the way up to Khamti at the foot of the Naga Mountains 800 kilometres to the north.

HIGHLIGHTS

– Relax under the sun and stars on the beaches of Myanmar’s Bay of Bengal coast: beautiful white-sand Ngapali, affordable Chaungtha, or the new kid on the block, Ngwe Saung.

– Hire a bicycle at any of these beaches and take a leisurely ride to explore nearby fishing villages for a taste of local lifestyles and seafood.

– Take a boat excursion on the Ayeyarwady River, from the hour-long trip to Mingun, to the six-hour float between Mandalay and Bagan, to a multi-day adventure from Myitkyina in Kachin State all the way down to Mandalay.