Welcome to South Sudan!

South Sudan, also called Southern Sudan, country located in northeastern Africa. Its rich biodiversity includes lush savannas, swamplands, and rainforests that are home to many species of wildlife. Prior to 2011, South Sudan was part of Sudan, its neighbour to the north. South Sudan’s population, predominantly African cultures who tend to adhere to Christian or animist beliefs, was long at odds with Sudan’s largely Muslim and Arab northern government. South Sudan’s capital is Juba.

South Sudan was settled by many of its current ethnic groups during the 15th–19th centuries. After the Sudan region was invaded in 1820 by Muḥammad ʿAlī, viceroy of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire, the southern Sudan was plundered for slaves. By the end of the 19th century the Sudan was under British-Egyptian rule. Although the north accepted British rule relatively quickly, there was greater resistance in the south. Because of this, British energies in the north were free to be directed toward modernization efforts, whereas in the south they were more focused on simply maintaining order, leading to a dichotomy of development between north and south that continued for several decades. After Sudan became independent in 1956, numerous governments over the years found it difficult to win general acceptance from the country’s diverse political constituencies, especially in the south. An early conflict arose between those northern leaders who hoped to impose the vigorous extension of Islamic law and culture to all parts of the country and those who opposed this policy.

History of South Sudan

Colonial administration

In 1899 the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was declared, providing for the Sudan to be administered jointly by Egypt and Great Britain, with a governor-general appointed by the khedive of Egypt but nominated by the British government. In reality, however, there was no equal partnership between Britain and Egypt in the Sudan, as the British dominated the condominium from the beginning. Their first order of business was to pacify the countryside and suppress local religious uprisings. The north was quickly pacified, and modern improvements were introduced under the aegis of civilian administrators, who began to replace the military as early as 1900. In the south, resistance to British rule was more prolonged; administration there was confined to keeping the peace rather than making any serious attempts at modernization.

Other than a revolt in 1924, led by a new generation of Western-educated Sudanese in the north, British rule in the Sudan remained unchallenged until after World War II. By then the growth of national consciousness among the educated Sudanese elite had led to the creation of the Graduates’ General Congress, which eventually demanded recognition by the British to act as the spokesman for Sudanese nationalism. The request was refused, and the Congress then split into two groups: a moderate majority and a radical minority. By 1943 the minority had won control of the Congress and organized the first genuine political party in the Sudan. The moderates then formed the Ummah (Nation) Party, with the intention of cooperating with the British toward independence.

British officials were well aware of the pervasive power of nationalism among the elite and sought to introduce new institutions to associate the Sudanese more closely with the task of governing. An advisory council was established for the northern Sudan, but Sudanese nationalists soon began to agitate to transform the advisory council into a legislative one that would include the southern Sudan. Previously, the British had facilitated their control of the Sudan by segregating the south’s predominantly animist or Christian Africans from the north’s predominantly Muslim Arabs. A decision to establish a legislative council was seen as a way to force the British to abandon that policy, which they ultimately did, and southern participation in the legislative council was instituted in 1947. Arabic was mandated the official language, however. That action generated much discontent in the southern Sudan, as English was long the primary language of education in the south, and using Arabic as the language of government severely limited the participation of southern Sudanese.

The creation of the legislative council elicited a strong reaction from the Egyptian government, which in October 1951 unilaterally abrogated a previous treaty and proclaimed Egyptian rule over the Sudan. Those hasty and ill-considered actions only served to alienate the Sudanese from Egypt. The situation changed after the 1952 Egyptian revolution. On February 12, 1953, the new Egyptian government signed an agreement with Britain granting self-government for the Sudan and self-determination within three years for the Sudanese. Elections for a representative parliament to rule the Sudan followed in November and December 1953. The Egyptians threw their support behind Ismāʿīl al-Azharī, the leader of the National Unionist Party (NUP), who campaigned to unite the Sudan with Egypt. That position was opposed by the Ummah Party, which had the less-vocal but pervasive support of British officials. To the shock of many British officials and to the chagrin of the Ummah, which had enjoyed power in the legislative council for nearly six years, Azharī’s NUP won an overwhelming victory.

Azharī formed the new government in January 1954, and the southern Sudanese, who had received a scant number of positions in the new administration, felt increasingly marginalized. Fears of northern domination led to widespread discontent in the south. On August 18, 1955, a number of southern army troops stationed in Torit mutinied after they were ordered to relocate to Khartoum in the north. Their rebellion was quickly put down, but the mutinous troops who were able to escape continued to agitate against the north. Their efforts to coordinate an armed resistance grew and became the basis of southern Sudan’s prolonged armed struggle against the north.

People of South Sudan

Ethnic groups

The people of South Sudan are predominantly Africans who for the most part are Christian or follow traditional African religions. The largest ethnic group is the Dinka, who constitute about two-fifths of the population, followed by the Nuer, who constitute about one-fifth. Other groups include the Zande, the Bari, the Shilluk, and the Anywa (Anwak). There is a small Arab population in South Sudan.

The Dinka are mostly cattle herders and can be found throughout much of the country, while the Shilluk are more-settled farmers and, like the Anywa, are concentrated in the east, although they too can also be found in other parts of South Sudan. The Nuer are concentrated in the centre-northeast of the country, while the Bari live farther south, not far from the border with Uganda. The Zande live in the southwest, close to the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Languages

The most important linguistic grouping in South Sudan is that of the Nilotes, who speak various languages of the Eastern Sudanic subbranch of the Nilo-Saharan language family. Chief among the Nilotic peoples are the Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, Bari, and Anywa. The Zande and many other smaller ethnic groups speak various languages belonging to the Adamawa-Ubangi branch of the Niger-Congo family of languages. Arabic, a Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic language family, is spoken by the country’s small Arab population and by others.

Under the 2005 interim constitution, both Arabic and English were official working languages, although English had been acknowledged as the principal language in what is now South Sudan since 1972 and was the most common medium for government business. The preference for English was made clear when South Sudan’s 2011 transitional constitution named it the official working language of the country and the language of instruction for all levels of education.

Religion

Christians, primarily Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Presbyterian, account for about three-fifths of South Sudan’s population. Christianity is a result of European missionary efforts that began in the second half of the 19th century. The remainder of the population is a mix of Muslims and those who follow traditional animist religions, the latter outnumbering the former. Although the animists share some common elements of religious belief, each ethnic group has its own indigenous religion. Virtually all of South Sudan’s traditional African religions share the conception of a high spirit or divinity, usually a creator god. There exist two conceptions of the universe: the earthly and the heavenly, or the visible and the invisible. The heavenly world is seen as being populated by spiritual beings whose function is to serve as intermediaries or messengers of God; in the case of the Nilotic peoples, these spirits are identified with their ancestors. The supreme deity is the object of rituals using music and dance.

Cultural Life of South Sudan

Cultural milieu

There are many different ethnic groups in South Sudan, each with a long history of customs and traditions. Despite a decades-long attempt by the northern-based national government of Sudan to “Arabize” the southern region in the 20th century, a rich cultural diversity still exists in South Sudan.

Daily life and social customs

Some aspects of South Sudan’s traditional cultures have weakened with the passage of time. Indeed, the advances of modern society, such as improved communications, opportunities for increased social and economic mobility, and the spread of a money economy, as well as decades of warfare and displacement, have led to a general loosening of the social ties, customs, relationships, and modes of organization in traditional cultures. Still, much from the past remains intact.

One of the most important forms of cultural expression among nonliterate groups in South Sudan is oral tradition. It is used as a vehicle for the creative expression of folklore and myths as well as for the recounting of history and traditions. It is also used as a font of guidance and advice for dealing with typical life events. Many South Sudanese groups mark the stages in the life cycle of the individual—birth, circumcision, puberty, marriage, and death—with ritual and ceremonial practices. Facial scarring and tattooing as methods of ritual adornment are common. Most groups observe patrilineal descent, but the significance of such agnatic ties among kin groups differs from one society to another. Polygyny is practiced in some groups and regarded as a means of extending affinal (in-law) relationships and acquiring support. Although divorce is now common, in the past a broken marriage was considered a shameful thing because it destroyed the network of relationships. Most groups have historically had some form of class distinction.

Cuisine varies throughout the country and among ethnic groups. Grains such as millet and sorghum are popular sources of sustenance and are supplemented by the variety of fresh fruits, vegetables, and legumes grown in the country, when available. Fish is a common source of protein among the riverine communities, whereas other groups rely more on meat and milk products from their livestock. A paste made from peanuts may accompany meats and vegetables. Examples of some foods and dishes enjoyed in the country include kisra, a wide flat bread that accompanies many meals, asida, a porridge made from sorghum that is often served with meat or vegetables, and ful, a dish with a basis of mashed fava beans and spices that may have various other foods added to it.

Western-style clothing is common, especially in cities and towns. Traditional dress varies throughout the country and among ethnic groups. Because of the hot climate, clothing tends to be loose-fitting and of light material.

Holidays observed in South Sudan include Sudan Independence Day on January 1 (marking Sudan’s independence from Great Britain and Egypt in 1956), Peace Agreement Day on January 9 (commemorating the signing of the 2005 CPA), SPLA Day on May 16 (marking the day in 1983 that the southern troops revolted, leading to a resumption in the fight for independence), and Martyrs’ Day on July 30 (the anniversary of the death of rebel leader John Garang de Mabior, used to commemorate the deaths of all those who died during the long-running civil war). The country’s large Christian population celebrates Easter and Christmas, and Christmas Day is a public holiday in South Sudan.

The arts

South Sudan’s various ethnic groups have a history of producing various handicrafts. The Zande, for example, were prominent as craftsmen and artists. Their superior material culture, particularly their knives, spears, and shields, was one of the factors by which they dominated their neighbours and brought about the spread of their culture. Basketry, net weaving, pottery, smelting, metalworking, and ivory and wood carving also were undertaken. Contemporary Zande are still noted for their iron, clay, and wood handicrafts. Some modern South Sudanese artists include painters who use acrylic, water, or oil paints.

Music is an integral part of the cultural traditions of South Sudan’s ethnic groups, as many ritual ceremonies are accompanied by singing and the playing of musical instruments. A variety of musical styles are enjoyed as entertainment in South Sudan. There is a traditional style of music, in which singers perform without musical accompaniment or with only a limited drumbeat. Western music styles, such as hip-hop and reggae, are popular. Also popular is a music style known as Sudanese or Sudanic fusion, which is a melding of Arabic and African rhythms. Dance is an integral part of the cultural traditions of South Sudan’s ethnic groups.

Cultural institutions

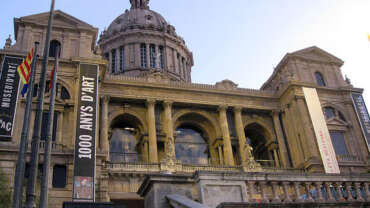

South Sudan has a rich, long cultural history. However, decades of marginalization by the northern-based government of Sudan, the long-running civil conflict, and the necessary focus on constructing basic infrastructure have meant that historically only limited resources could be devoted to cultural institutions. There is the Nyakuron Cultural Centre in Juba, which hosts many cultural and social events. The mausoleum of rebel leader John Garang, also in Juba, is a site of importance.

Explore South Sudan

The world’s youngest nation: South Sudan. Independent since 2011, after years of war against the government of Sudan, our newest country is one of the most ethnically diverse in the world. But its tourism industry is at a barely nascent state, and you can’t pioneer more then that!

If any travellers do make it to South Sudan they usually only stay in Juba for one or two days and then leave, having “been to” South Sudan. But we offer more then that and bring you a genuine South Sudanese experience by getting out of the very strictly controlled Juba and visiting not one but three ethnic communities of South Sudan. This trip will give you more than a glimpse of the country but also offer you much more freedom than you would have with a simple trip to Juba, where photos are strictly not allowed. We can expect incredible encounters with warm locals and to see things very few have seen.

Our trip starts with a full tour of the strange boom-town capital that is Juba. We will take in its limited sites but also witness the full melting-pot of cultures that is South Sudan.

Our trip then takes us to the incredible Mundari tribes, herders who literally live in the wild in symbiosis with their cattle. They are unmistakable by the fact that they cover their whole body in chalk-like makeup, making them look like ghosts. After visiting the Mundari, we will visit of the Dinka, which are a majority in South Sudan and nicknamed the tallest people in the world. The Dinka’s contribution to the struggle for independence was enormous, and here too we will spend a day mingling with them and truly seeing what their life is like.