Welcome to beautiful Sweden!

Sweden is a Scandinavian nation with thousands of coastal islands and inland lakes, along with vast boreal forests and glaciated mountains. Its principal cities, eastern capital Stockholm and southwestern Gothenburg and Malmö, are all coastal. Stockholm is built on 14 islands. It has more than 50 bridges, as well as the medieval old town, Gamla Stan, royal palaces and museums such as open-air Skansen.

History of Sweden

Earliest settlements

The thick ice cap that covered Sweden during the last glacial period began to recede in the southern region about 14,800 years ago. A few thousand years later the earliest hunters in the region began following migratory paths behind the retreating ice field. The stratified clay deposits that were left annually by the melting ice have been studied systematically by Swedish geologists, who have developed a dependable system of geochronology that verifies the dates of the thaw. The first traces of human life in Sweden, dating from about 9000 BCE, were found at Segebro outside Malmö in the extreme southern reaches of Sweden, but earlier settlement could have been facilitated by land bridges between present-day Denmark and southern Sweden that existed from about 13,100–12,700 and 12,100–10,300 years ago. Finds from the peat at Ageröd in Skåne dated to 6500 BCE reveal a typical food-gathering culture with tools of flint and primitive hunting and fishing equipment, such as the bow and arrow and the fishing spear. New tribes, practicing agriculture and cattle raising, made their appearance about 2500 BCE, and soon afterward a peasant culture with good continental communications was flourishing in what are now the provinces of Skåne, Halland, Bohuslän, and Västergötland. The so-called Boat-Ax culture (an outlier of the European Battle-Ax cultures) arrived about 2000 BCE and spread rapidly. During the Neolithic Period, southern and central Sweden displayed the aspects of a homogeneous culture, with central European trade links; in northern Sweden the hunting culture persisted throughout the Stone and Bronze ages.

Settlers became familiar with copper and bronze around 1500 BCE. Information about Sweden’s Bronze Age has been obtained by studying rock carvings and relics of the period, as, for example, the ornate weapons of chieftains and other decorative items preserved in the earth. The early Bronze Age (c. 1500–1000 BCE) was also characterized by strong continental trade links, notably with the Danube River basin. Stone Age burial customs (skeleton sepulture, megalithic monuments) were gradually replaced by cremation. Rock carvings suggest a sun cult and fertility rites. Upheavals on the continent, combined with Celtic expansion, seem to have interrupted (c. 500 BCE) bronze imports to Scandinavia, and a striking poverty of finds characterizes the next few centuries. The climate, comparatively mild since the Neolithic Period, deteriorated, necessitating new farming methods. At this time, iron reached the north.

For the early Iron Age (c. 400 BCE–c. 1 CE) the finds are also relatively scanty, showing only sporadic contacts with the La Tène culture, but they become more abundant from the Roman Iron Age (c. 1 CE–400) onward. The material from this period shows that Sweden had developed a culture of its own, although naturally reflecting external influences.

Trade links between the Roman Empire and Scandinavia gave Rome some knowledge of Sweden. The Germania (written 98 CE) of Tacitus gives the first description of the Svear, or Suiones (Swedes), stated to be powerful in men, weapons, and fleets. Other ancient writers who mention Scandinavia are Ptolemy, Jordanes, and Procopius.

The Viking Age

At the beginning of this period a number of independent tribes were settled in what is now Sweden, and their districts are still partly indicated by the present divisions of the country. The Swedes were centred in Uppland, around Uppsala. Farther south the Götar lived in the agricultural lands of Östergötland and Västergötland. The absence of historical sources makes it impossible to trace the long process by which these provinces were formed into a united and independent state. The historical events leading to unification are reflected darkly in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf—which gives the earliest known version of the word sveorice, svearike, sverige (Sweden)—and also in the Old Norse epic Ynglingatal, contained in the Heimskringla of Snorri Sturluson.

As a result of Arab expansion in the Mediterranean area in the 8th and 9th centuries, the trade routes along the Russian rivers to the Baltic Sea acquired enhanced importance. In the second half of the 9th century, Swedish peasant chieftains secured a firm foothold in what is now western Russia and Ukraine and ruthlessly exploited the Slav population. From their strongholds, which included the river towns of Novgorod and Kiev, they controlled the trade routes along the Dnieper to the Black Sea and Constantinople (now Istanbul) and along the Volga to the Caspian Sea and the East. Trade in slaves and furs was particularly lucrative, as the rich finds of Arab silver coins in Swedish soil demonstrate. Swedish Vikings also controlled trade across the Baltic; and it was for this activity that Birka, generally regarded as Sweden’s oldest town, was founded (c. 800). Swedish Vikings took part in raids against western Europe as well. From the 10th century, however, control of the Russian market began to slip from Swedish hands into those of Frisian, German, and Gotland merchants.

Christianization

The first attempt to Christianize Sweden was made by the Frankish monk Ansgar in 830. He was allowed to preach and set up a church in Birka, but the Swedes showed little interest. A second Frankish missionary was forced to flee. In the 930s another archbishop of Hamburg, Unni, undertook a new mission, with as little success as his predecessors. In Västergötland to the southwest, Christianity, introduced mainly by English missionaries, was more generally accepted during the 11th century. In central Sweden, however, the temple at Uppsala provided a stronghold for pagan resistance, and it was not until the temple was pulled down at the end of the 11th century that Sweden was successfully Christianized.

The struggle between the old and new religions strongly affected the political life of Sweden in the 11th century. Olaf (Olof Skötkonung), who came from Västergötland but proclaimed himself ruler of all Sweden during the early 11th century, was baptized in Skara about the year 1000. He supported the new religion, as did his sons Anund Jakob (reigned c. 1022–c. 1050) and Edmund (c. 1050–60). The missionaries from Norway, Denmark, and even Russia and France, as well as from Hamburg, won converts, especially in Götaland, the area where the royal dynasty made its home and where early English missionaries had prepared the ground. Many pagans refused to abandon their old faith, however, and civil wars and feuds continued. Claimants vied for the throne until the mid-13th century, when a stable monarchy was finally achieved.

The 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries

When and where Sweden originated have long been matters of debate. Some historians contend that the cradle of Sweden is located in Västergötland and Östergötland—i.e., in the southwestern and southeastern parts of the country. Others maintain that Sweden was founded in the Lake Mälar region in Uppland by the Svear, who subjugated the central provinces and eventually conquered the provinces of Götaland. Evidence indicates, however, that, at the end of the Viking era in the 11th century, Sweden remained a loose federation of provinces. The local chieftains from time to time proclaimed themselves rulers over all Sweden, when in reality each formally exerted power only over his own province. It appears that the Swedish provinces were first united in the 12th century. The oldest document in which Sweden is referred to as a united and independent kingdom is a papal decree, by which Sweden in 1164 became a diocese with its own archbishop in Uppsala.

Sweden in the 12th century consisted of Svealand and Götaland, which were united into a single kingdom during the first half of that century, while the provinces of Skåne, Halland, and Blekinge in the south belonged to Denmark; Bohuslän in the west, along with Jämtland and Härjedalen in the north, were part of Norway. About 1130 Sverker, a member of a magnate family from Östergötland, was acknowledged as king, and this province now became the political centre of Sweden. Sverker sided with the church and established several cloisters staffed by French monks; he was murdered about 1156. During the later years of Sverker’s reign, a pretender named Erik Jedvardsson was proclaimed king in Svealand; little is known about Erik, but according to legend he undertook a crusade to Finland, died violently about 1160, and was later canonized as the patron saint of Sweden.

Civil wars

Erik’s son Knut killed Sverker’s son (1167) and was accepted as king of the entire country. Knut organized the currency system, worked for the organization of the church, and established a fortress on the site of Stockholm. After his death in 1196, members of the families of Erik and Sverker succeeded each other on the throne for half a century. While the families were battling for the throne, the archbishopric at Uppsala was established, and the country was organized into five bishoprics. The church received the right to administer justice according to canon law and a separate system of taxation, protected by royal privileges, and the pretenders sought the church’s sanction for their candidacies. The first known coronation by the archbishop was that of Erik Knutsson in 1210. The church also gave its sanction to the “crusades” against Finland and the eastern Baltic coast; the action combined an attempt at Christianization with an attempt at conquering the areas.

By the mid-13th century the civil wars were drawing to an end. The most important figure in Sweden at that time was Birger Jarl, a magnate of the Folkung family. The jarls (earls) organized the military affairs of the eastern provinces and commanded the expeditions abroad. Birger was appointed jarl in 1248 by the last member of the family of St. Erik, Erik Eriksson, to whose sister he was married. Birger’s eldest son, Valdemar, was elected king when Erik died (1250). After Birger defeated the rebellious magnates, he assisted his son in the government of the country and gave fiefs to his younger sons. Birger was in fact ruler of the country until he died in 1266. During this time central power was strengthened by royal acts that were binding throughout Sweden, in spite of the existence of local laws in the provinces. The acts promulgated included those giving increased protection to women, the church, and the thing (“courts”) and improving the inheritance rights of women. By a treaty with Lübeck in 1252, Birger promoted the growth of the newly founded city of Stockholm. At the same time, the Hanseatic merchants received privileges in Sweden, and the establishment of towns blossomed.

In 1275 Valdemar was overthrown by his brother Magnus I (Magnus Ladulås) with the help of a Danish army. In 1280 a law was accepted establishing freedom from taxes for magnates who served as members of the king’s cavalry, creating a hereditary nobility; the following year Magnus Ladulås exempted the property of the church from all taxes. Under Magnus’s reign the position of jarl disappeared and was replaced by the drots (a kind of vice king) and the marsk (marshall), together with the established kansler (chancellor). The export of silver, copper, and iron from Sweden increased trade relations with Europe, especially with the Hanseatic cities.

Magnus died in 1290 and was succeeded by his 10-year-old son, Birger. The regency was dominated by the magnates, especially by the marsk, Torgils Knutsson; even after Birger’s coronation in 1302, Torgils retained much of his power. The king’s younger brothers Erik and Valdemar, who were made dukes, attempted to establish their own policies and were forced to flee to Norway (1304), where they received support from the Norwegian king; the following year the three brothers were reconciled. A new political faction was created by the leaders of the church, whom Torgils had repressed, together with a group of nobles and the dukes, and in 1306 the marsk was executed. Birger then issued a new letter of privileges for the church, but his brothers captured and imprisoned him. Two years later the kings of Denmark and Norway attacked Sweden on his behalf. Birger was again recognized king of Sweden at a peace concluded in 1310 with Denmark and Norway, but he was forced to transfer half of the kingdom to his brothers as fiefs. Erik’s territory, together with his earlier acquisitions, then consisted of western Sweden, northern Halland, southern Bohuslän, and the area around Kalmar and stretched across the borders of the three Scandinavian kingdoms. In 1312 the dukes married two Norwegian princesses, increasing their power and dynastic position; but in December of 1317 the dukes were imprisoned by their brother following a family dinner, and they died in prison. The nobility rebelled against Birger, who was forced to flee to Denmark in 1318, and the king’s son was executed.

Code of law

The magnates now seized control of Sweden and reasserted their power to elect a king. They chose Magnus, the three-year-old son of Duke Erik, who had shortly before inherited the crown of Norway. In connection with the election, the privileges of the church and the nobility were confirmed, and the king was not to be allowed to raise taxes without the approval of the council and the provincial assemblies. The magnates now revised the laws of Svealand and, by the Treaty of Nöteborg (1323), established the Finnish border with Russia. The Danish province of Skåne was bought and put under the Swedish king; by 1335 Magnus ruled over Sweden, including Skåne and Blekinge, Finland, and Norway, to which he soon added Halland. During Magnus’s reign a national law code was established (c. 1350), providing for the election of the king, preferably from among the royal sons, and a new town law code was written that gave the German merchants considerable privileges. In 1344 Magnus’s elder son Erik was elected heir to the Swedish throne, one year after his younger brother Haakon received the crown of Norway. Erik made common cause with the nobility and his uncle, Albert of Mecklenburg, against his father; and in 1356 Magnus was forced to share the kingdom with his son, who received Finland and Götaland. Two years later Erik died, and the kingdom was again united under Magnus’s rule.

In his struggles with the nobles, Magnus received the support of the Danish king, Valdemar Atterdag, and in 1359 Magnus’s son Haakon of Norway was engaged to Valdemar’s daughter Margaret. The following year Valdemar attacked Skåne, and Magnus relinquished Skåne, Blekinge, and Halland in return for Valdemar’s promise of help against Magnus’s Swedish enemies. In 1361 Valdemar attacked Gotland and captured Visby, an important Baltic trading centre. Haakon, who had been made king of Sweden in 1362, and Margaret were married in 1363. Magnus’s opponents among the nobility went to Mecklenburg and persuaded Duke Albert’s son, also named Albert, to attack Sweden; Magnus was forced to flee to Haakon’s territory in western Sweden. In 1364 the Folkung dynasty was replaced by Albert of Mecklenburg (1363–89). Albert joined in a coalition of Sweden, Mecklenburg, and Holstein against Denmark and succeeded in forcing Valdemar Atterdag from his throne for several years. Albert was not as weak as the nobles had hoped, and they forced him to sign two royal charters stripping him of his powers (1371 and 1383). At the end of the 1380s Albert had plans to reassert his power, primarily by recalling the royal lands that had been given to the nobles; in 1388 the Swedish nobles called upon Margaret, now regent of Denmark and Norway, for help. In 1389 her troops defeated and captured Albert, and she was hailed as Sweden’s ruler. Albert’s allies harried the Baltic and continued to hold out in Stockholm, and it was only in 1398 that Margaret finally won the Swedish capital. In 1396 her great-nephew Erik of Pomerania, then about age 16, became nominal king of Sweden, and the following year he was hailed and crowned king of Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, marking the beginning of the Kalmar Union.

The Kalmar Union

Sweden had entered the Kalmar Union on the initiative of the noble opponents of Albert of Mecklenburg. After Margaret’s victory over Albert and his allies, the national council announced its willingness to return those royal estates that had been given to its members during Albert’s reign, and Margaret succeeded in carrying out the recall of this property. She remained popular with the Swedes throughout her reign, but her successor, Erik, who took real power after her death in 1412, appointed a number of Danes and Germans to administrative posts in Sweden and interfered in the affairs of the church. His bellicose foreign policy caused him to extract taxes and soldiers from Sweden, arousing the peasants’ anger. His war with Holstein resulted in a Hanseatic blockade of the Scandinavian states in 1426, cutting off the import of salt and other necessities and the export of ore from Sweden, and led to a revolt by Bergslagen peasants and miners in 1434. The rebel leader, Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson, formed a coalition with the national council; in 1435 a national meeting in Arboga named Engelbrekt captain of the realm. Erik agreed to change his policies and was again acknowledged as king of Sweden by the council. Erik’s agreement was not fulfilled to the Swedes’ satisfaction, however, and in 1436 a new meeting at Arboga renounced allegiance to Erik and made the nobleman Charles (Karl) Knutsson captain of the realm along with Engelbrekt. Soon after, Engelbrekt was murdered by a nobleman; Charles Knutsson became the Swedish regent, and in 1438 the Danish council deposed Erik, followed in 1439 by the Swedish council.

The Danish council elected Christopher of Bavaria as king in 1440, and Karl Knutsson gave up his regency, receiving, in return, Finland as a fief, whereupon the Swedish council also accepted Christopher. He died in 1448 without heirs, and Charles Knutsson was elected king of Sweden as Charles VIII of Sweden. It was hoped that he would be accepted as the union king, but the Danes elected Christian of Oldenburg. The Norwegians chose Charles as king, but a meeting of the Danish and Swedish councils in 1450 agreed to give up Charles’s claims on Norway, while the councils agreed that the survivor of Charles and Christian would become the union king or, if this was unacceptable, that a new joint king would be elected when both were dead. Charles refused to accept this compromise, and war broke out between the two countries. In 1457 the noble opposition, led by Archbishop Jöns Bengtsson Oxenstierna, rebelled against Charles, who fled to Danzig. Oxenstierna and Erik Axelsson Tott, a Danish noble, became the regents, and Christian was hailed as king of Sweden. Christian increased taxes, and in 1463 the peasants in Uppland refused to pay and were supported by Oxenstierna, whom Christian then imprisoned. The bishop of Linköping, a member of the Vasa family, led a rebellion to free the archbishop, and Christian’s army was defeated. Charles was recalled from Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) and again became king, but within six months difficulties between him and the nobles, especially Oxenstierna and the bishop of Linköping, forced him to leave the kingdom. Oxenstierna served as regent from 1465 to 1466 and was succeeded by Tott; the battles between the two families led to the recall of Charles, who ruled from 1467 to his death in 1470.

People of Sweden

Ethnic groups

Although different groups of immigrants have influenced Swedish culture through the centuries, the population historically has been unusually homogeneous in ethnic stock, language, and religion. It is only since World War II that notable change has occurred in the ethnic pattern. From 1970 to the early 1990s, net immigration accounted for about three-fourths of the population growth. By far, most of the immigrants came from the neighbouring Nordic countries, with which Sweden shares a common labour market.

In the 1980s Sweden began to receive an increasing number of asylum seekers from Asian and African countries such as Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, Eritrea, and Somalia, as well as from Latin American countries that were suffering under repressive governments. Then from 2010 to 2014 the number of people seeking asylum in Sweden expanded dramatically, reaching more than 80,000 in 2014, and that number doubled to more than 160,000 in 2015. Many of these people were fleeing the Syrian Civil War. From the beginning of that conflict, Sweden had granted residency to any Syrian seeking asylum (some 70,000 in total). Thus, by 2016 one in six Swedish residents had been born outside the country, and Sweden, feeling the strain of the mass influx of migrants, enacted new and more stringent immigration restrictions.

Sweden has two minority groups of indigenous inhabitants: the Finnish-speaking people of the northeast along the Finnish border, and the Sami (Lapp) population of about 15,000 scattered throughout the northern Swedish interior. Once a hunting and fishing people, the latter group developed a reindeer-herding system that they still operate. Most of the Sami in Sweden have other occupations as well.

Languages

Swedish, the national language of Sweden and the mother tongue of approximately nine-tenths of the population, is a Nordic language. It belongs to the North Germanic (Scandinavian) subgroup of the Germanic languages and is closely related to the Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faeroese languages. It has been influenced at times by German, but it has also borrowed some words and syntax from French, English, and Finnish. A common standard language (rikssvenska) has been in use more than 100 years. The traditionally varying dialects of the provinces, although homogenized rapidly through the influences of education and the mass media, are still widely spoken. Swedish is also spoken by about 300,000 Finland-Swedes. Swedish law recognizes Sami and Finnish (both of which belong to the Uralic language group), as well as Meänkieli (the Finnish of the Torne Valley), Romani, and Yiddish as national minority languages, along with sign language. About 200 languages are now spoken in Sweden, owing to immigrants and refugees.

Religion

Prehistoric archaeological artifacts and sites—including graves and rock carvings—give an indication of the ancient system of religious beliefs practiced in Sweden during the pre-Christian era. The sun and seasons figured largely, in tandem with fertility rites meant to ensure good harvests. These practices were informed by a highly developed mythic cycle, describing a distinctive cosmology and the deeds of the Old Norse gods, giants, and demons. Important gods included Odin, Thor, Freyr, and Freyja. Great sacrificial rites, thought to have taken place every eight years at Old Uppsala, were described by the author Adam of Bremen in the 11th century.

Sweden adopted Christianity in the 11th century, and for nearly 500 years Roman Catholicism was the preeminent religion. Sweden was the home to St. Bridget, founder of the Brigittine convent at Vadstena. As the first waves of the Protestant Reformation swept Europe in the mid-1500s, Lutheranism took hold in Sweden and remained dominant. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden was the official state church until 2000, and between three-fifths and two-thirds of the population remains members of this church. Since the late 1800s a number of independent churches have emerged; however, their members can also belong to the Church of Sweden. Immigration has brought a steady increase to the membership of the Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Islamic religions. Judaism is the country’s oldest global non-Christian religion, practiced in Sweden since 1776. After Christianity, Islam is the largest religion in Sweden, with about 100,000 active practitioners at the turn of the 21st century, although the number of Swedes of Muslim heritage was nearly three times that number.

Cultural Life of Sweden

Cultural milieu

Sweden’s cultural heritage is an interweaving of a uniquely Swedish sensibility with ideas and impulses taken from other, larger cultures. As a result, Swedish culture has long been characterized by a push and pull. Swedish art, poetry, literature, music, textiles, dance, and design are deeply infused with a primal relationship with the Nordic landscape and climate, but Swedes also have long been attracted to the greatness of the cultures of such countries as France and Germany, and influences from these and other European cultures have contributed to the development of Swedish literature, fashion, and cultural debate, as well as to the Swedish language itself.

As Swedish political influence grew, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, so did a desire among prominent Swedes for their country to take a place at centre stage with other important European cultures. This refusal to be classified as a cultural backwater remains a strong force today. At the same time, simplicity is a hallmark of Swedish culture, as is openness to new thoughts and trends. There is also a sense of wit and playfulness combined with candor and sincerity that is apparent not only in the works of Swedish cultural icons such as Selma Lagerlöf, August Strindberg, Ingmar Bergman, Astrid Lindgren, and Carl Larsson but also in Swedish folk music and folk art.

War-weary and largely nonaligned since the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century, Sweden embraced a neutrality and peacefulness that permitted the state in the 20th century to broadly support arts and culture politically, educationally, and economically. During the last half of the 20th century, Sweden welcomed immigrants and refugees who brought with them their own cultural traditions, which have informed the broader Swedish culture. The effects of American popular culture have also been widely felt in Sweden. A rebirth of contemporary Swedish creativity has attracted worldwide attention both in those art forms in which Swedes have traditionally thrived—literature and film—and in design, popular music, photography, fashion, gastronomy, and textiles.

Genuine rural folk traditions are disappearing in urban areas as a result of increasing settlement; however, since the 1990s there has been a resurgence of interest in those traditions among many Swedes who live in towns and cities. Still vital in Gotland, Dalarna, and various other areas are special national costumes, dances, folk music, and the like. Spring is celebrated on the last night of April with bonfires and song across the country. This is a great students’ festival in university towns such as Uppsala and Lund. The bright Midsummer Eve is celebrated around June 21, about the time of the year’s longest day (see solstice). In the ceremony a large pole, decorated with flowers and leaves, is placed into the ground and danced around. Some celebrations have a religious association: Advent, St. Lucia’s Day, Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide. Pagan elements are still sometimes evident in these holiday ceremonies. The Lucia candlelights are a relatively recent but very popular custom performed for St. Lucia’s Day on the morning of December 13, at almost the darkest time of year; the ceremony features a “Light Queen,” who, wearing a white gown and a crown of lighted candles, represents the returning sun.

Immigration, travels abroad, and imports have changed and internationalized the Swedish cuisine. However, the original Swedish buffet of appetizers known as a smörgåsbord remains a national favourite. The typical Swedish kitchen reflects the harsh northern climate, with fresh food available only during the short but intense summer season. In the words of the mother of Swedish cuisine, 18th-century cook Cajsa Warg, “You take what you get.” Swedish culinary traditions reflect the importance of being able to preserve and store food for the winter. Lutefisk (dried cod soaked in water and lye so it swells), pickled herring, lingonberries (which keep well without preservatives), knäckebröd (crispbread), and fermented or preserved dairy products such as the yogurtlike fil, the stringy långfil, and cheeses all reflect this need for foods that will keep through the colder parts of the year. Twisted saffron-scented buns called lussekatter and heart-shaped gingersnaps are served along with coffee in the early morning. Christmas is celebrated on December 24 with the traditional Julskinka ham. Glogg, a mulled, spiced wine, is also enjoyed during this season.

The arts

J.H. Roman, an 18th-century composer, has been called the father of Swedish music, but the Romantic composer Franz Berwald received wider acclaim for his 19th-century symphonies and other works. Notable 20th-century composers include the “Monday group,” who were inspired by the antiromantic Hilding Rosenberg in the 1920s and drew also upon leading modern composers from abroad. The vital Swedish folk song has been developed further by a number of musicians. The lively and often moving ballads and “epistles” of Carl Michael Bellman, an 18th-century skald, are still widely performed and enjoyed in contemporary Sweden. A number of Swedish opera singers, among them Jenny Lind, Jussi Björling, and Birgit Nilsson, gained renown throughout the world. Popular music, especially the Europop of the internationally celebrated group ABBA, and music production, editing, and advertising were major Swedish exports from the late 1970s on. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Swedish songwriter and producer Max Martin played a pivotal role in the success of several American hitmakers, including the Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears. Moreover, in addition to making a national specialty of the heavy metal genre of “death” metal in the late 1980s and early ’90s, Sweden also produced a number of other performers and groups who achieved international pop music success in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, among them Ace of Base, the Hives, I’m from Barcelona, Peter Bjorn and John, and the Tallest Man on Earth.

Few names in Swedish literature were well known internationally until the 19th century, when the writings of August Strindberg won worldwide acclaim. He is still generally considered the country’s greatest writer. In the early 20th century, novelist Selma Lagerlöf became the first Swedish writer to win the Nobel Prize. A favourite poet in Sweden is Harry Martinson, who, writing in the 1930s, cultivated themes and motifs ranging from the romantic Swedish countryside to those concerned with global and cosmic visions. Other poets such as Karin Boye and Tomas Tranströmer have international reputations. In contemporary Swedish literature such authors as Kerstin Ekman, P.C. Jersild, Lars Gustafsson, Sara Lidman, Canadian-born Sven Delblanc, Henning Mankell, and Mikael Niemi have found a wide audience. Activist and journalist Stieg Larsson did not start writing fiction until later in his life, and though his literary career was cut short by his death by heart attack in 2004, he dazzled readers worldwide with a series of detective novels that included Män som hatar kvinnor (2005; “Men Who Hate Women”; Eng. trans. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), helping to set the stage for international appreciation of Swedish and Scandinavian crime fiction. One of the most widely published and translated modern Swedish writers is Astrid Lindgren, noted for her children’s books, including the famous Pippi Longstocking series. (For more information on Swedish literature, see the article Scandinavian literature.)

Swedish theatre, opera, and ballet are multifaceted. Birgit Cullberg attained international fame as director of the Swedish Royal Ballet in Stockholm. The Swedish cinema was pioneered in the silent and early sound eras by actor-director Victor Sjöström. Like Sjöström, director Ingmar Bergman moved from the stage to motion pictures, gaining critical acclaim outside Sweden with his film Wild Strawberries (1957). Subsequently, as many of both his earlier and later films became classics of international cinema, Bergman was hailed as one of the most important filmmakers of all time. Among other Swedes who have made major contributions to the art of filmmaking are actors Greta Garbo, Ingrid Bergman, Bibi Andersson, and Max von Sydow, cinematographer-director Sven Nykvist, and director Lasse Hallström. In the last decades of the 20th century, Lars Norén shouldered the mantle of Sweden’s national dramatist.

Modern Swedish visual art was inspired by late 19th-century romantic nationalism, originating with such painters as Carl Larsson, Anders Zorn, and Bruno Liljefors. Carl Milles dominated monumental sculpture in the 1920s. At the Paris World’s Fair in 1925, an important connection was established between Swedish industry and designers who had both academic art education and popular handicraft tradition. Superb results have been achieved in ceramics, woodwork, textiles, silver, and stainless steel. Sweden is also renowned for its leadership in glass and furniture design. Many famous glass designers such as Bertil Vallien, Ingegerd Råman, and Ulrica Hydman-Vallien (part of the Orrefors Kosta Boda group) and independent glass artists such as Ulla Forsell, Mårten Medbo, and Frida Fjellman have won international acclaim. Moreover, Sweden has been a world leader in industrial design, blending sound ergonomics, aesthetics, and high functionality. IKEA, perhaps Sweden’s best-known company, disseminates design in a thoroughly “Swedish” way all over the world.

Cultural institutions

The country’s cultural institutions are subsidized through state funding. Cultural activities reach all parts of the country through traveling companies devoted to theatre, concerts, and exhibitions. Despite state support, the majority of these cultural offerings are also dependent on private funding.

Every municipality has a public library where books are loaned free of charge. The libraries are often centres for other cultural events as well. Scientific libraries, including the largest ones, like the University of Uppsala library and the Royal Library, are also open to the public. Sweden has one of the highest library lending rates in the world.

There are about 300 museums and local heritage centres in Sweden. About 20 museums are run by the state; most of them are national museums in Stockholm. Besides the national museums for art, history, natural history, and folklore, the open-air Skansen historical park (founded in 1891) enjoys worldwide interest. In addition, there are county museums with regional responsibility. Sweden has a number of institutional theatres, including Stockholm’s Royal Opera and Royal Dramatic Theatre, both of which have held performances since the 1780s.

Several major professional symphony orchestras and chamber orchestras, along with many smaller musical institutions, form the backbone of musical life. The state supports the production of literature, films, and sound recordings, as well as art for public buildings.

Learned societies play an important role as independent promoters of arts and sciences. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, founded in 1739, is engaged in worldwide cooperative programs. It also selects Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics. The Nobel Prize for Literature is awarded by the Swedish Academy, which was inaugurated together with the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities by King Gustav III in 1786. The Nobel Prize award ceremony, held on December 10 each year, is the single most heralded annual event held in Sweden. It is arranged by the Nobel Foundation, which administers the funds and other properties from the estate of Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.

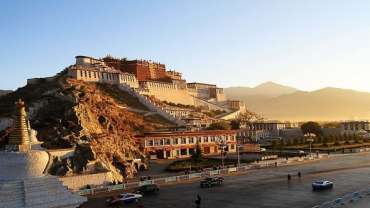

Discover Stockholm

Stockholm is known as one of the most inclusive and welcoming cities in the world. Its contemporary, urban appeal is balanced with centuries-old history and closeness to nature. As for the things to do in Stockholm, the list is endless.

Spreading idyllically across a Baltic Sea archipelago of fourteen islands, it’s easy to see why the Swedish capital of Stockholm has acquired the nickname “Venice of the north”. It seems as if wherever you look, your gaze is met by water.

Located on Sweden’s southeast coast, Stockholm weather changes according to four distinct seasons. Summers are warm – sometimes quite hot – and it rarely gets dark during summer nights. The winters may be mild and rainy but can also be quite cold and snowy. The colours of autumn are spectacular in the city parks, and spring is welcomed by locals, wrapped in blankets and sipping a drink, at outdoor restaurants and cafés.

The city is easy to get around on foot or public transport, and its various districts have their own unique vibes – the island of Södermalm has a laid-back air and is a draw for the creative set, while Östermalm is the picture of refined elegance. Nestling between these two areas, Norrmalm is a busy and vibrant downtown spot, and you’ll find the charming Old Town (Gamla Stan) south of Norrmalm.

Stockholm was officially founded in 1252 by the regent of Sweden, Birger Jarl. By the end of the 13th century, Stockholm had grown to become Sweden’s biggest city, serving as the country’s political centre and royal residence – one that was repeatedly besieged over the following centuries. King Gustav Vasa is forever celebrated for recapturing Stockholm in 1523 from the temporary rule of the King of Denmark.

Stockholm of today is a tolerant, inclusive society that is welcoming of everyone. Stockholm Pride festival, the biggest of its kind in the Nordic region, is a definite calendar highlight attracting tens of thousands of LGBTQ visitors from across the country and the globe each summer.

A forward-thinking, innovative city, Stockholm is home to a growing tech-innovation community and a large number of start-ups – a density only Silicon Valley can compete with. Music streaming company Spotify is only one example of the global names hailing from the city; its headquarters is still based in the centre of the town.